Is Private Credit Coming to Early Stage Venture?

In a world where private credit is booming, early stage companies are hitting revenue milestones faster, and AI startups are growing leaner than predesseors, can early-stage startups tap into private credit without repeating the mistakes of venture debt?

To answer that, we spent the past several weeks unpacking the rise of private credit, its relationship to venture debt, and whether a new playbook is forming: one where structured credit may become a meaningful part of the capital stack. We hope this piece may serve as a conversation starter to explore more alternative financing methods.

Private credit is a non-bank loan made directly to a company. The loan is typically negotiated privately, structured flexibly, and typically secured by some form of cash flow, revenue, or asset based.

In this piece you'll learn about:

- Rise of Private Credit

- Private Credit's Relationship to Venture Debt

- Examples of Private Credit Structures

- Risks and Tradeoffs

- Whether a new playbook could form, especially for leaner AI companies

The Rise of Private Credit

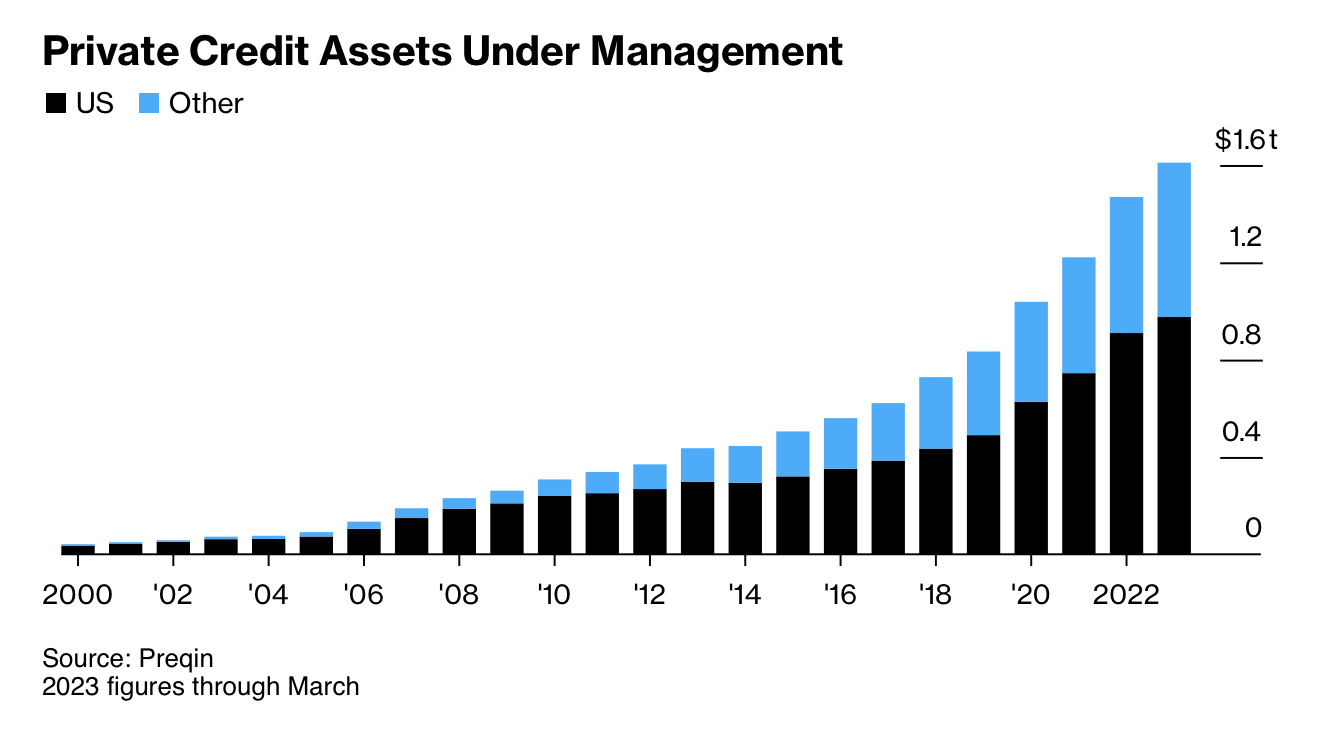

In recent years, private credit surpassed $1.7 trillion (according to KKR), with firms like Oaktree, Blackstone, and Apollo aggressively expanding their lending arms.

Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan both called private credit one of their top growth areas for the next decade.

Increasingly, we see that private credit AUM has been steadily increasing not just in the U.S., but external markets as well.

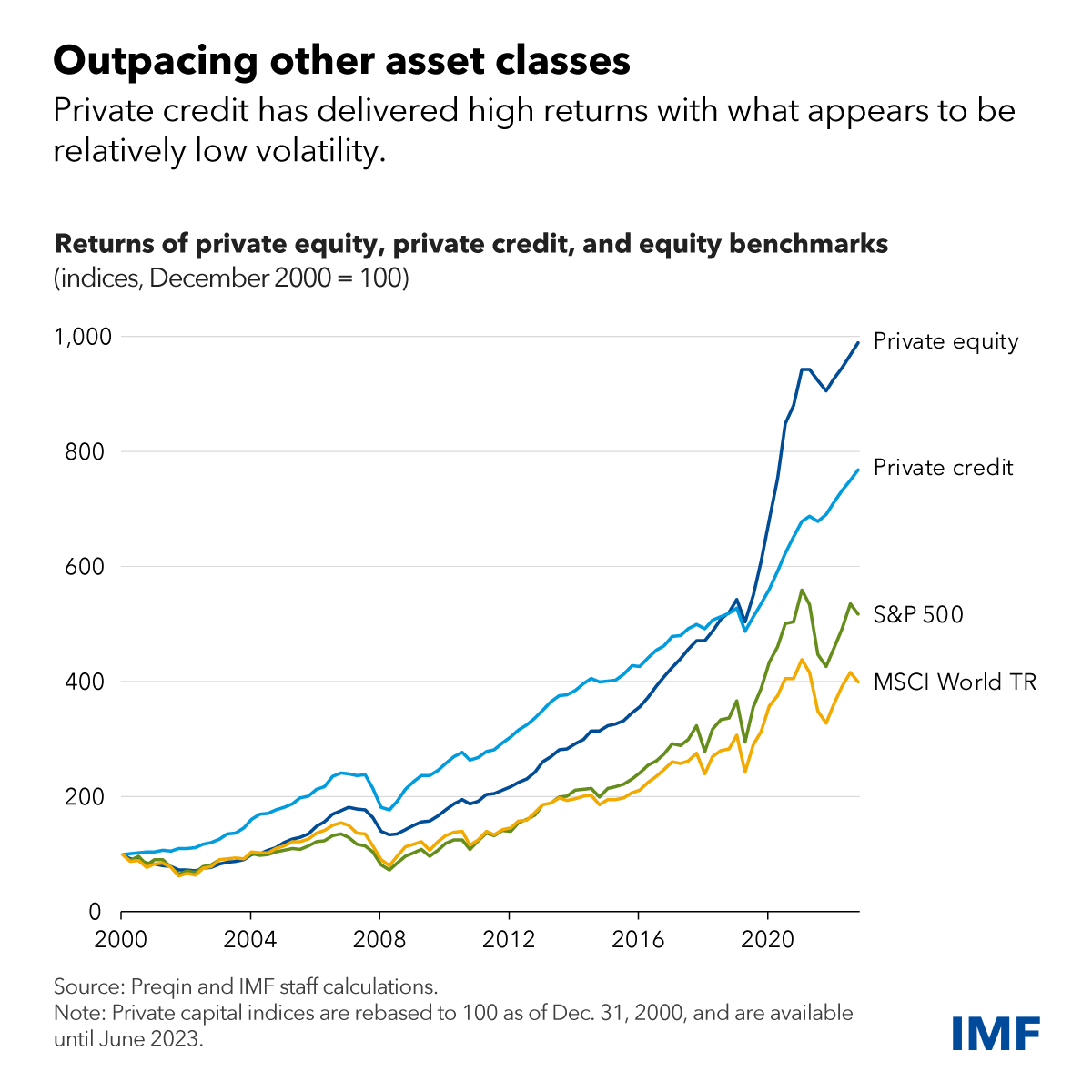

Data from the IMF also shows that, in addition to increasing levels of AUM, private credit performance itself has surged in recent years, surpassing the S&P 500 and eclipsed only by private equity.

What are the reasons for the surge?

Higher Interest Rates Increase the Attractiveness of Private Credit

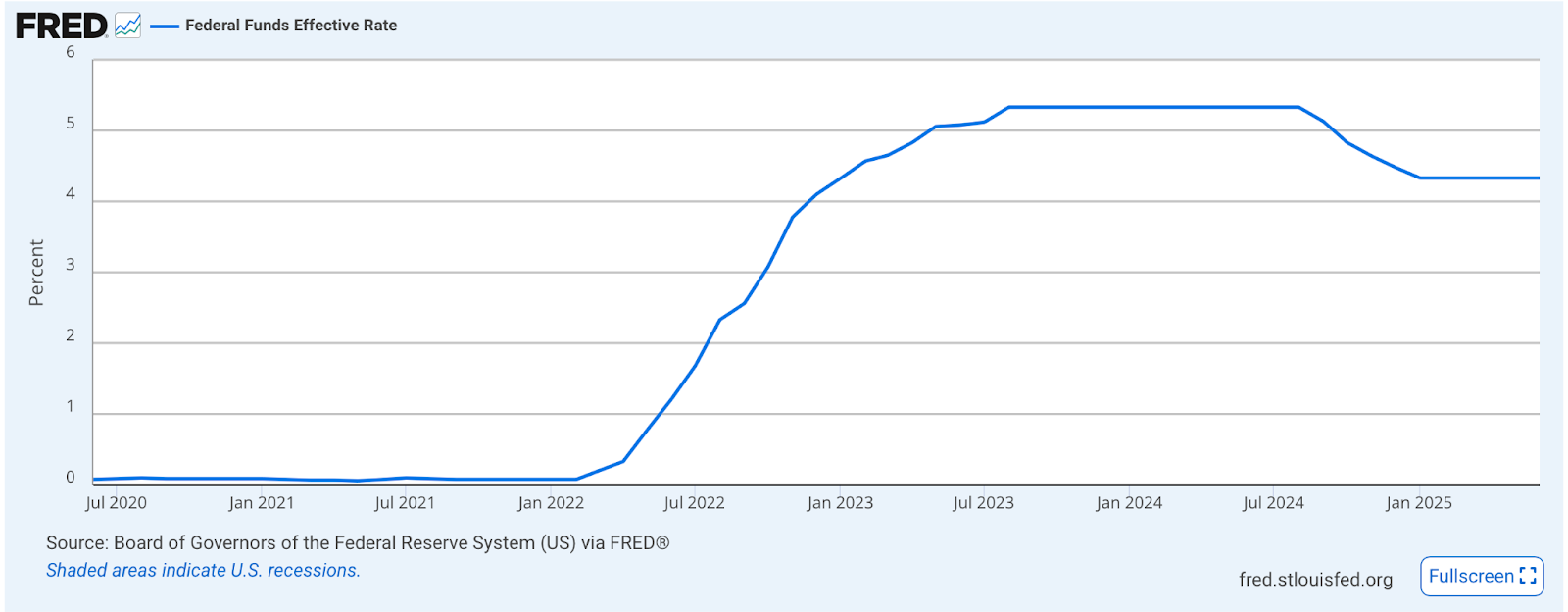

Data from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) visualizes the rise in rates on a trailing 5-year basis.

For one, in a period categorized by rising interest rates, investors (especially institutional ones like pension funds and endowments) are on the hunt for higher-yielding assets. Most private credit instruments are tethered to floating interest rates, so when interest rates rise, investors in said instruments stand to benefit.

Higher interest rates also have a tendency to reduce the competition in the lending market. For example, when rates are higher, banks tend to lend less. Banks naturally pull back because the risk of default increases, regulatory capital costs increase, and alternative assets (like treasury bills) appear more attractive. On the demand side, the cost of capital is higher, which makes projects and acquisitions look less profitable.

A Slower IPO Market = Less Access to Capital

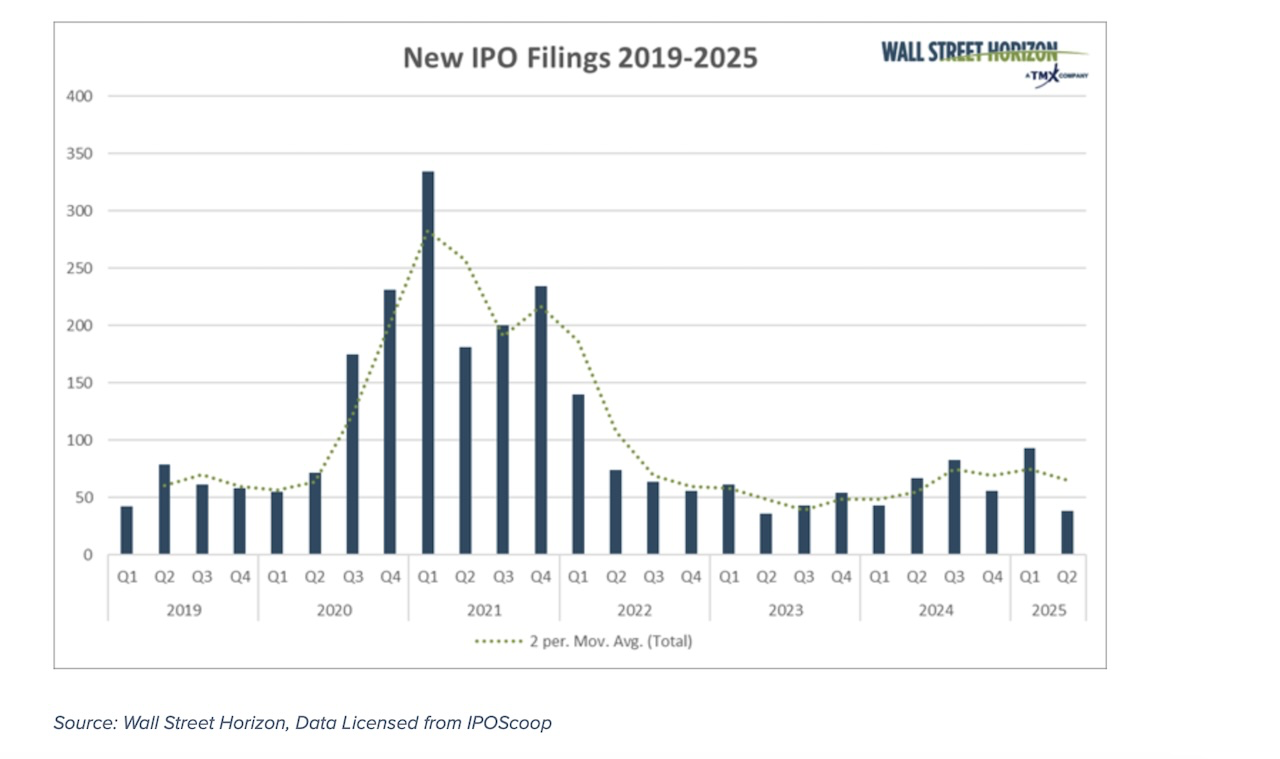

Secondly, a general slowdown in the IPO market has led to companies searching for capital. In the absence of access to public markets, private credit has helped fill that void.

When IPO markets slow down, this dries up a major source of equity capital. Instead of selling shares, companies can turn to private credit for funding, which can allow them to extend runway, bridge to profitability, or delay IPO plans.

A Structural Shift Post-2008 GFC

Part of the recent surge has also been structural in nature. As a result of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, regulators started to impose stricter compliance guidelines on banks, especially riskier and smaller loans. The Dodd-Frank act, passed in 2010, imposed higher capital requirements to banks, required regular stress-testing and oversight on financial institutions, and more. This led to a systemic pullback from lending to middle-market businesses and other non-investment grade borrowers. This made way for a structural opening for non-bank lenders, such as Blackstone, Ares, Apollo, and Oaktree.

So far, the private credit boom has largely focused on later-stage companies or in more traditional sectors like infrastructure, healthcare, and cash-flowing software rollups. But a new question is emerging in early-stage ventures: can private credit actually work for startups at the seed or Series A stage?

Venture Debt vs. Private Credit

Private credit and venture debt may sound similar (especially when private debt is a phrase used interchangeably with private debt), the two asset classes are distinct in many facets.

.png)

Unlike traditional loans, there’s no public issuance, no underwriting committee, and often no standardized terms. Think of it as bespoke capital: money designed to match a business’s specific risk profile and repayment ability. In the early-stage context, that could look like a line of credit backed by ARR, a revenue-share agreement, or a milestone-based loan tied to product or GTM execution.

The core idea is this: if a startup is generating money, or has visibility into near-term revenue, it may not need to sell equity. It can borrow, repay over time, and maintain a clean cap table via a private credit facility.

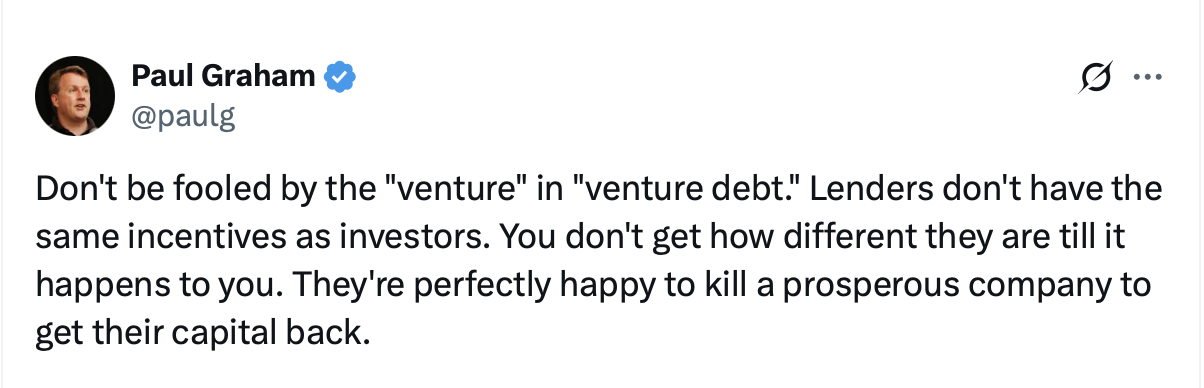

Venture debt, on the other hand, has historically been a more rigid solution, and has maintained a relatively negative reputation in venture circles. See Paul Graham's comments below:

Venture debt normally entails a loan tied to a startup’s valuation and fundraising momentum, not necessarily its financial performance. It often includes warrants, meaning it’s not truly non-dilutive, and comes with repayment timelines and covenants that can be unforgiving if growth slows.

For years, venture debt was seen as a cheap way to extend runway. But, when startups missed projections or faced down rounds, venture debt turned from tool to trap with defaults, restructurings, and uncomfortable board conversations.

The biggest difference? Venture debt assumes a growth path and external validation, with solutions offering little to no flexibility. Private credit assumes variability and underwrites what’s actually under the hood, but with a higher degree of flexibility and customization.

While venture debt and private credit may look similar (both are forms of borrowed capital), they operate on fundamentally different assumptions. Venture debt is tethered to a startup’s fundraising momentum, often requiring a priced equity round and including dilution through warrants. Private credit, by contrast, is grounded in a company’s actual business performance by underwriting recurring revenue, cash flow, or assets, and is typically non-dilutive.

One bets on valuation; the other bets on revenue.

How Private Credit Can Be Different

Here’s where private credit becomes interesting, especially for early-stage startups in an ecosystem increasingly focused on business fundamentals, an earlier strive toward profitability, and a more cognizant approach toward cap table and equity management.

As startups get leaner, more operationally “fit,” and increasingly focused on achieving profitability, a shift that would’ve felt almost contrarian just a few years ago, private credit begins to look not just viable, but preferable to equity fundraising. In an environment where every dollar is scrutinized and founders are more protective of dilution, the idea of raising capital without giving up ownership (especially when that capital is tied to real business fundamentals like ARR or gross margin) suddenly feels like a competitive advantage.

Private credit facilities, done right, can be more flexible, founder-aligned, and use-case specific than traditional venture debt. Private credit isn’t just venture debt rebranded. Structurally, it’s more flexible and philosophically, it’s more founder-aligned. And most importantly, it’s underwritten based on a startup’s actual cash flows, assets, or contractual revenue and not simply its last valuation.

In the early-stage context, private credit can take the form of recurring revenue credit lines, IP-backed loans, revenue-share agreements, milestone-based facilities, or even a combination of all of the above. Rather than relying on a lead investor’s term sheet to greenlight a loan, lenders can assess the startup’s financials directly, often via real-time integrations with billing systems like Stripe or QuickBooks. It’s credit built for operational visibility, not just investor signaling.

And in contrast to venture debt’s "loan + warrant" model, many private credit deals in the early-stage ecosystem are entirely non-dilutive. That makes them particularly attractive to capital-efficient founders who want to preserve ownership while still funding growth.

What an Early-Stage Deal Might Look Like

At the early stage, most private credit facilities can be highly customizable. Below are some examples of what a PC facility can look like at the early-stage:

1. Revenue-Based Financing (RBF)

The borrower pays back a fixed multiple of the principal (e.g. 1.3x–1.7x), repaid via a percentage of monthly revenue. The faster you grow, the faster you repay.

Example: A $1M loan at 1.5x repayment, repaid via 5% of monthly revenue until $1.5M is repaid.

Upside: Non-dilutive, aligned with performance.

Risk: Effective APR can get steep, especially if growth stalls.

2. Milestone-Based Tranches

A $2M facility is structured in $500K increments, released upon hitting growth or product milestones.

Upside: Encourages discipline. Reduces over-capitalization.

Risk: Missed milestones = dry powder remains locked.

3. ARR-Backed Lines of Credit

Popular with SaaS businesses. Lenders underwrite ARR, not equity. Lines scale with revenue, with limits at 25–50% of ARR.

Example: $4M ARR → $1–2M in credit, typically at 10–13% interest.

Upside: High alignment with SaaS business model.

Risk: Concentrated customer churn can trigger reassessment or line freeze.

4. IP or Contract-Backed Lending

For deep tech or bio startups, lenders underwrite patents, licensing deals, or government contracts.

Upside: Monetizes illiquid but valuable assets.

Risk: Hard to value; very lender-specific underwriting.

So Why Now?

In many ways, the timing makes sense. Equity capital is more expensive today than it was in 2021. Down rounds and flat rounds are more common, and founders are increasingly ownership-conscious.

Meanwhile, interest rates remain elevated, which means that for lenders (particularly those with structured finance experience), the yield on early-stage credit deals can be compelling. Paired with an increased focus on business fundamentals and profitability being a north-star, private credit can almost seem preferable to equity in some cases.

Just as important: real-time financial visibility is now a reality, thanks to API-native tooling across accounting, billing, and ops. That unlocks better underwriting, tighter monitoring, and more adaptive repayment structures.

Risks and Tradeoffs

Still, private credit at the early stage is not without risk. Effective interest rates can be high, particularly when structured as revenue-share agreements or short-term facilities. Flexibility on paper doesn’t always translate to flexibility in execution; founders unfamiliar with credit may underestimate the financial weight of regular repayments, or the implications of default clauses tucked into dense legal documents.

And then there’s the macro question: if growth stalls and equity remains expensive, will these facilities become a bridge, or a trap? Capital structure complexity is rarely the source of a startup’s success, and too much debt too early can cloud downstream fundraising, especially if new investors perceive it as a sign of weakness rather than capital efficiency.

But if structured thoughtfully, private credit doesn’t have to crowd out equity. It can complement it. And in a market where liquidity is scarce and capital is cautious, optionality itself is a competitive advantage.

What This Means for Early-Stage VC

For Behind Genius, our perspective is that private credit may present a systemic shift (similar to secondaries), and can open up new frontiers. It gives a way to help founders extend runway, preserve ownership, and experiment with growth models without immediately reaching for a priced round. It may also allow VCs to structure “hybrid” deals: pairing small equity checks with tailored credit components, especially for companies with clear revenue paths but light capital needs.

It’s still early. But we’re seeing the contours of a new capital stack, one that blends equity, secondaries, and private credit, and all designed to meet startups where they are, rather than where the market thinks they should be.